Every night, my father would sit at his typewriter and write his scripts. Our family lived in New York City in Manhattan in a large apartment. My room was next to my father’s office. It was this clacking that sent me to sleep at night; this noise evokes a man deeply immersed in his work. In later years the typewriter was replaced by an electric machine that was also eventually replaced by a word processor. Whatever tool was needed most for his work, he learned it.

My father was a diligent researcher. At first glance, his office would look very cluttered. But he knew and could tell you where to find that slip of paper he needed. It was from my father that I learned how to research. To want to know the what and why of life, to know that someone’s story and history mattered. These skills and understandings have served me very well. Especially when I was at the American Museum of Natural History as a team member creating the Hall of Asian Peoples.

He and my mother used to talk out stories, to review his scripts. They debated. Sometimes they would start talking in the living room, then walk around our apartment, and would end up in the kitchen. Seeing them work together, supporting each other, helped me support others when I had to do so. My mother was an artist in her own right and later changed careers from dancer to special education teacher. My father and all of us helped my mother get through school and attain her Master’s Degree in Special Education. At times he would type her school papers and edit them, too, which generated another form of debate between them. Underneath this was a genuine love of each other’s skills and a love for words and learning.

Getting a play produced in New York takes stamina, faith and grit. The project is your own but not your own in many ways. My father told me he decided early on, as a writer, to see his work as a collaboration. He was known for his ability to adapt words and change ideas as needed. An ability polished by decades of writing in radio, television, documentary films and in Hollywood. But when the need arose he could speak up for his ideas, words and language. These acts of writing were the thread that held his creativity together.

His office was too small to contain his research library. The dining room became an extension of his office with ceiling high bookcases filled with knowledge and history. This love of history served him well, in the years he took to write Bully. He read many books about Theodore Roosevelt (aka TR). He spoke to experts at the Theodore Roosevelt Association and attended meetings. He and my mother went to TR’s houses in Sagamore Hill, Oyster Bay and Manhattan. Those studies did enable him to get “inside” TR’s heart and mind. It was a person’s heart that was equally important to him. My father was determined to show different sides of TR’s complex nature. The play’s title spoke to that energy and fire. TR used the word “Bully” to express his joy and enthusiasm for someone or something — a completely different use of the word than we know today.

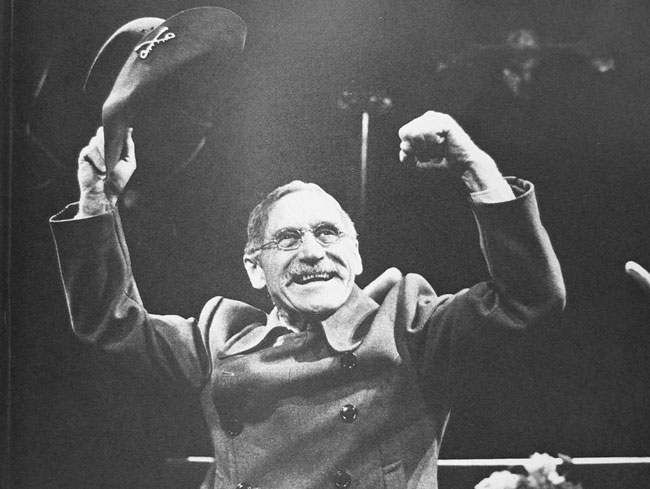

Attending many performances, my imagination took flight as the characters in this one-man show conjured through my father’s script and James Whitmore’s (TR) love for this play revealed themselves to my heart. The theater was alive for me. TR became alive to me. I began to care about what happened to him and his family. Even today, in reading the play or seeing the tape from the play on PBS, my attention is captured and I relive his story. It’s always been an amazement to me that James Whitmore did not wear any stage makeup in playing the role. He used the play and his deep acting ability to create his performance; a performance that showed me the magic of the theater and how each person is linked to another. For me it was a direct experience in perseverance, creativity and love. My father made his dream to be a working writer come true for himself and those who knew him.

To learn more about licensing a production of Bully, click here.

Noël Coward’s Travels

Kate Chopin in New Orleans: Mother-Daughter Author Duo Collaborate on Historical Book