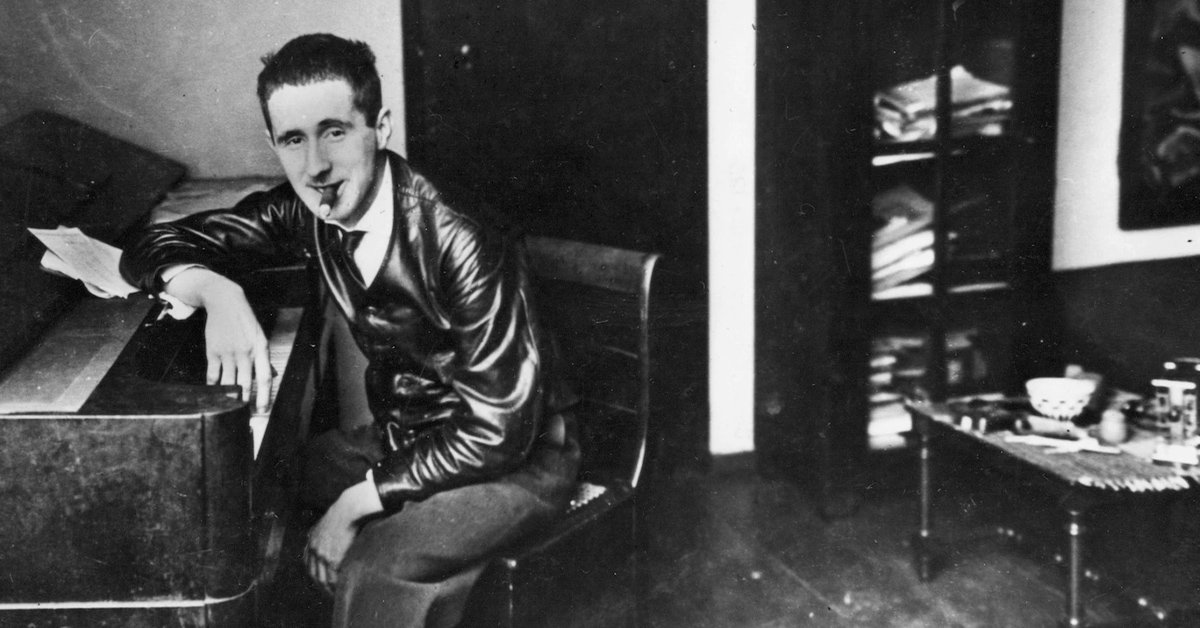

A German playwright, poet and theatre practitioner, Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) championed what he called “dialectical theatre” as the ideological and social platform for his leftist causes. He promoted naturalistic acting as a mirror of what was happening in society, breaking away from the norm of “cathartic theatre.” Brecht felt that when an audience believed in the action onstage, they became too emotionally involved with the characters, losing the ability to think and to judge critically. He famously criticized audiences, saying they “hang up their brains with their hats in the cloakroom.”

To help audiences to remain objective and emotionally distant, Brecht created the “epic theatre,” using a range of theatrical devices or techniques (the Verfremdungseffekt, or estrangement effect) to remind the audience they are watching a piece of theatre – a presentation of life, not real life itself. In Brecht’s plays, the alienation prevents the audience from becoming too emotionally involved with the characters. The fourth wall is broken down, and the actors directly address and acknowledge the audience.

Here are five examples of Brecht’s work, from an early play to his most celebrated creations.

…

Baal (1918)

Baal was the first of four full-length plays that Brecht wrote in Bavaria before moving to Berlin. The play, about a the decline of a drunken poet, was inspired by Brecht’s own experience in the pubs of Augsburg. Though its initial publisher refused to publish the work due to concerns of censorship, Baal was later published by Gustav Kiepenhauser in Potsdam in 1922. Baal and two other completed plays were awarded the prestigious Kleist Prize. The literary award’s citation noted that Brecht’s language “is vivid without being deliberately poetic, symbolical without being over literary. [He] is a dramatist because his language is felt physically and in the round.” Unfortunately, the premiere performances of Baal in Leipzig in 1923 did not achieve huge commercial success.

Brecht’s writing at this period had a strong element of insurrection; most of it was directed against his own upbringing in the middle class, as evidenced in Baal‘s sarcastic opening scene. On the other hand, Expressionism declined in the late 1910s to early 1920s; Brecht’s writing mirrored that decline and coincided with the rise of Neue Sachlichkeit, a coolly representational and socially conscious style. The title character, a traveling poet, remains a romantic-expressionist figure, despite the playwright’s intention to protest the Expressionists’ acknowledgement of humanity.

In his 1930s doctrine of “alienation,” Brecht noted:

“I hope in Baal and In the Jungle I’ve avoided one common artistic bloomer, that of trying to carry people away. Instinctively, I’ve kept my distance and ensured that the realisation of my (poetical and philosophical) effects remains within bounds.”

These English translations of the play are available for licensing from Concord Theatricals:

-

Baal, translated by Christopher Logue (UK)

-

Baal, translated by Ralph Manheim and William Smith (UK)

-

Baal, translated by Peter Tegel (UK)

-

Baal, translated by John Willett (UK)

Fear and Misery of the Third Reich (1938)

This overtly anti-Nazi play consists of 24 scenes of life in Vienna between 1933 and 1938, before Hitler’s entry into the city. Each scene is based on reports from the inside, preceded and linked by a short verse, forming a sort of kaleidoscope of life under Nazi dictatorship. Brecht’s powerful work was influenced by the rise and impact of European Fascism and the Moscow-based Communist International (Comintern).

At the world premiere at the Salle d’Iéna in Paris in May 1938, the play was presented under the title 99%, alluding to the popular support for Hitler in the elections of March 1936. This version included only eight scenes, and the ending dramatized the vote for the annexation of Austria, which had taken place just two months before the performance. In his first collaboration with Brecht, Paul Dessau wrote the accompaniment music. This version, sadly, was lost. Critics praised the two performances, and the play cemented Brecht’s dedication to epic theatre, forcing audiences – who were personally experienced in the political turmoil depicted onstage – to distance themselves from the drama, instead viewing and evaluating the play’s ideas objectively.

Fear and Misery employs several features of epic theatre: the writing remains distant and the scenes are presented not in ‘acts’ or ‘parts’ but in chronological order. The characters’ petty everyday actions and cruel attitudes towards each other remain powerful and striking to current audiences, who know too well the outcome of Hitler’s pre-Auschwitz campaign.

These English translations of the play are available for licensing from Concord Theatricals:

-

Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, translated by Eric Bentley (US/UK)

-

Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, translated by Paul Kriwaczek (UK)

-

Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, translated by John Willett (UK)

Mother Courage and Her Children (1939)

In this chronicle play of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), the resilient Mother Courage and her children endure twelve years of the early 17th-century holy war, traveling through Sweden, Poland, Finland, Bavaria and Italy. The play’s world premiere in Zurich in 1941 was attended by a star-studded crowd, including Thornton Wilder.

The language of the play is lively, vividly portraying a world at war and the people who must survive within it. Brecht crafted the character of Mother Courage with a striking voice and features, cre

ating a star vehicle for the many venerable actresses who have played the role over the ensuing decades. Reflecting neither 17th-century language nor modern everyday speech, her dialogue is its own cynical lingo. Rife with elisions and using few conjunctions, it highlights the anxiety of the character and reflects the intense pressures of the war. As the war claims all of Mother Courage’s children, one by one, the play poignantly demonstrates that no one can profit from war without being subject to its terrible cost.

The playwright hoped the Berliner Ensemble revival production would help audiences reflect on the damage inflicted by Hitler’s government, enabling them to rebuild their shattered culture and reconnect with the Weimar Republic’s progressive ideas. Ultimately, he hoped to encourage the next generation of creatives—who were not subverted by the Nazi regime—to make theatre. The play remains one of the most influential and celebrated works of the 20th century.

These English translations of the play are available for licensing from Concord Theatricals:

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Eric Bentley (US/UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by David Hare (US/UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Lee Hall (UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Michael Hofmann and John Willett (UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Hanif Kureishi (UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Tony Kushner (UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Ralph Manheim (US/UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Robert David MacDonald (UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by Peter Watson (UK)

-

Mother Courage and Her Children, translated by John Willett (UK)

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1941)

This satirical allegory is a more oblique critique of the Nazis. Though it was written for the American stage and envisioned in largely American terms, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui was never seen by an American audience while Brecht lived. Exploring the violence, drama and immorality of Chicago’s gangster world, particularly the brotherhood between gangsters and businessmen in the green grocer trade, Brecht drew a parallel between Chicago gangsters and Hitler’s fight for power.

Characters in the play are based on actual historical figures, including President Hindenberg (Dogsborough), Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s chief propagandist and vice chancellor (Givola), and Ernst Röhm, the leader of the Brownshirts (Ernesto Roma). Through murder, blackmail and intimidation, the play explains how the fascist regime came to power.

Brecht invited his audience to equate the kind of low-level brutality that flourished under police regimes with the grander threat of war and the murder of political opponents. His biting satire cautioned that small-time, everyday violence could lead to a resurrection of Fascism on a grand scale. As relevant today as the day it was written, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui remains a striking reflection on the possibility of a Fascist resurgence.

These English translations of the play are available for licensing from Concord Theatricals:

-

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, translated by Ranjit Bolt (UK)

-

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, translated by Andy de la Tour (UK)

-

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, translated by Ralph Manheim (UK)

-

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, translated by Stephen Sharkey (UK)

-

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, translated by George Tabori (US/UK)

The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1944)

One of Brecht’s most celebrated and performed plays, The Caucasian Chalk Circle was originally written for Broadway. The story is based on the biblical tale of Solomon and the two mothers arguing over the rightful charge of a child. In the bible story, Solomon wisely decrees that the child be cut in half, forcing the true mother to offer the whole baby to her competitor instead. In Brecht’s version, a chalk circle is drawn around the child; the baby will belong to the first person to remove it from the circle.

The plot is organized as a play within a play, encouraging the use of Brecht’s epic theatre techniques. All scenes are self-contained. The play has a strong sense of circularity, with the conclusion leading back to the start. The last line, “The valley to the waterers, so that it bears fruit,” refers back to the Prologue, wherein the fruit farmers are given the valley. The communist message is delivered right at the beginning in the Prologue, and the moral message is strengthened as the audience watch the story of Grusha and the Chalk Circle unfold.

These English translations of the play are available for licensing from Concord Theatricals:

-

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, translated by W.H. Auden, James Stern and Tania Stern (UK)

-

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, translated by Alistair Beaton (UK)

-

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, translated by Eric Bentley (US/UK)

-

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, translated by Thulani Davis and William R. Spiegelberger (US)

-

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, translated by John Holmstorm (UK)

-

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, translated by Ralph Manheim (US/UK)

-

The Caucasian Chalk Circle, translated by Frank McGuinness (UK)

…

Bertolt Brecht’s theories and stage works have continued to influence the views of contemporary playwrights and audiences for decades. In his book Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic (1964), the playwright summaries his dramatic conventions of epic theatre. His pioneering works in promoting naturalistic theatre bequeathed a whole generation of Brechtian directors, writers and actors to theatres of both the East and West.

Notably excluded from this list are the following plays:

-

A Respectable Wedding (1919) (UK)

-

Driving Out a Devil (1919) (UK)

-

Lux in Tenebris (1919) (UK)

-

The Catch (1919) (UK)

-

The Beggar or the Dead Dog (1919) (UK)

-

Drums in the Night (1920) (UK)

-

The Threepenny Opera (1927)

-

The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1929)

-

The Mother (1931) (UK)

-

Round Heads and Pointed Heads (1934) (UK)

-

The Horatians and the Curiatians (1934) (UK)

-

Señora Carrar’s Rifles (1937) (UK)

-

The Jewish Wife, amalgamated from the scenes in Fear and Misery in the Third Reich (1938) (UK)

-

How Much Is Your Iron? (1939) (UK)

-

Dansen (1939) (UK)

-

The Trial of Lucullus (1939) (UK)

-

The Duchess of Malfi (1943) (UK)

-

Antigone (1947) (UK)

-

The Days of the Commune (1949) (UK)

-

The Trial of Joan of Arc at Rouen (1952) (UK)

-

Turandot (1954) (UK)

Works inspired by Brecht:

…

To license a production of Bertolt Brecht’s work, visit the Concord Theatricals website in the US or UK.

Noël Coward’s Travels

Kate Chopin in New Orleans: Mother-Daughter Author Duo Collaborate on Historical Book